Category: social issues

Muhammad Yunus wins the Nobel peace prize for providing micro credit to the poor in Bangaladesh. The Economist discusses his achievements, as well as microfinance in general, and their impact on eradicating poverty.

Macro credit: Muhammad Yunus has won the Nobel peace prize for his role in promoting financial services for the poor

Oct 19th 2006, from the Economist print edition.

Also available online with a subscription. Click here

FOR many of the supporters of Muhammad Yunus and the institution he created, the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh, the announcement that the two will share a Nobel peace prize is long overdue—the only surprise is that it was so long in coming. Grameen's website lists 60 awards, 27 honorary degrees, and 15 other “special honours” previously received by Mr Yunus directly, and seven received by Grameen. The selection committee said the prize was for developing what “had appeared to be an impossible idea”, namely loans to people who lack collateral.

Mr Yunus has unquestionably helped create an industry that provides financial services to the poor, combining his experience of growing up in a small village with his academic background as an economist to popularise what was once just a fringe area of banking and an obscure idea about alleviating poverty. Grameen has become a sizeable institution, with 6.7m customers, most of them women and all of them poor. Grameen has, by its own reckoning, distributed $6 billion in loans, each on average less than $200. Dressed in a traditional Bangladeshi outfit made by a Grameen affiliate, the charismatic Mr Yunus, with his soft voice and warm smile, can transform the dry, grinding mechanics of banking into a bewitching story about beggars, children and empowered women, all benefiting from credit that should be a human right and could even, he says, end poverty.

Even so, loans to the poor have existed for thousands of years. The formalised system of small borrowing that Mr Yunus pushed in Bangladesh beginning in the mid-1970s was being tried in bits and pieces around the world at the same time, and earlier as well. Even in Bangladesh, where his award was warmly received as an international endorsement, there are two other equally large and innovative microfinance institutions: BRAC, which dates back to the same era as Grameen, and ASA, which came later but improved on the basic model. Yet as remarkable as these three are, to single them out is, in a sense, unfair. There are thousands of financial institutions around the world providing financial services to the very poor. It is a world of extraordinary individuals, and one that has advanced as a result of collective insights. Physics and chemistry, to cite two other Nobel categories, may be built upon the shoulders of a few giants, but microfinance needs—and has—thousands of them.

Mr Yunus and Grameen succeeded by seizing an idea, expanding quickly, proselytising and resisting the temptation to move beyond the poor. His particular approach to microfinance has not, however, been without controversy. By legend, Grameen grew out of a $27 loan Mr Yunus made in 1974 to a woman manufacturing furniture who did have credit, but at an exorbitant price. Grameen emerged soon thereafter, based on several key operational techniques: loans were made to individuals but through small groups who in effect (if not explicitly) had joint liability; the loans were for business, not consumption; and collection was frequent, usually weekly. Interest charges were significant—the money was not aid, and a fundamental tenet of Grameen is that the poor are creditworthy—but the rates were relatively low (currently just above 20%).

This approach had virtues and limitations. Low rates and lower savings (except as a back-up for repayment) meant that in its early years, Grameen relied on capital from public and private donors—something that less charismatic or connected entrepreneurs than Mr Yunus found hard to replicate. Joint liability for loans became an increasing problem for groups when some members wanted to borrow more than others. And it was unclear whether the money received really did always go to business, rather than daily needs. A deeper question is just how helpful such tiny loans really are. Heart-warming case studies abound, but rigorous analyses are rare. The few studies that have been done suggest that small loans are beneficial, but not dramatically so. A further question is whether an approach emphasising credit really can eradicate poverty: a ridiculously ambitious goal, though one that Mr Yunus's evangelical view of the virtues of credit has perpetuated. Whether this form of lending has led to peace, the presumptive reasoning behind the award, is just as big an unanswered question.

Credit where credit's due

The classic Grameen model began to fray in the 1990s and hit a wall in 1998, when a devastating flood pushed up losses and people began missing weekly payment meetings. Mr Yunus was no doubt familiar with microfinance innovations in other countries: BRI in Indonesia had transformed itself from a wreck into a huge success by emphasising savings, not credit, and other institutions had started to abandon group lending. Grameen restructured in 2001, emphasising savings (deposits now exceed loans) and relying less on joint liability for groups.

With Grameen now thriving and the Nobel on the shelf, what will Mr Yunus do next? There are persistent rumours that he might enter politics, given his prestige within Bangladesh. And this could be a good time for him to step away from microfinance, which appears to be at an inflection point. Institutions continue to emerge and grow, many funded by private capital and seeking a real return, an approach Mr Yunus opposes. They often begin by charging higher rates than Mr Yunus considers legitimate, but cut prices when their returns draw competitors—a tough but theoretically more supple model. Microfinance would also benefit from a voluntary regulatory structure to improve its access to capital, and greater use of technology to reduce transaction costs. What it needs, in short, are the boring, quiet innovations that dynamic industries depend upon, but which, alas, do not win prizes. The Nobel, and its recognition of microfinance's most charismatic cheerleader, may mark the end of an era as a more mature industry starts to emerge.

------------------------------

Personal response

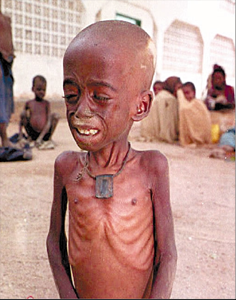

photo: The orion “Don’t waste food. The children in Nigeria are starving.” I only really understood my mum’s oft-repeated rhetoric when I saw poverty, in all its disgrace, for myself.

photo: The orion “Don’t waste food. The children in Nigeria are starving.” I only really understood my mum’s oft-repeated rhetoric when I saw poverty, in all its disgrace, for myself. I was in Beijing on an exchange programme last December. One evening, as I walked down a filthy street, burying my hands away from the icy gale, in the snug comfort of my pockets, I noticed a scrawny man - with a stump for his right hand – shiver in the bitter cold in his filthy cardbox “home”. He only had a tattered (and probably scavenged) bedsheet for warmth. Hesitating, I decided he wasn’t one of those I had been warned about, and rummaged in my haversack (chock full with cheap shopping) for some shirts to offer to him. The gratitude in his eyes pierced my conscience. Hopefully, they would keep him warm.

Born into prosperity - and all its luxuries - I consider myself blessed. I know not what it is like to be poor and hungry. All I know it that it isn’t nice – and that that’s an understatement.

The root of dystopia

Looking at the affluent first world, capitalism seems to work as an economic model. But it’s far from a panacea. It causes extreme polarization. 1.1 billion worldwide subsist on less than US$1 a day (see endnote 1). The very concept of survival of the fittest, which makes capitalism successful, also makes it cruel. While the fittest survive, the rest, like that disabled man in Beijing, languish. The race to riches has sidelined many.

The poor world is also plagued with a deluge of problems – ranging from political turmoil (Bangladesh) to civil war (Iraq) and even genocide (Sudan). These only exacerbate an already dire situation via direct damage and killing off what little economic opportunities there are.

Hope of a better age

It is only right that we, on the greener pasture, emerge from our selfish disinterest and help the poverty-tormented.

But throwing money at the problem won’t work. Aid is only temporary relief; it doesn’t make the poor any richer. When donor fatigue sets in, the poor are often left to rot (see footnote 2). To reap sustainable long-term benefits, on a scale much greater than what aid can do, the poor must stand on their own two feet: they need to sort out their domestic bedlam, and develop their economy. Education is key to escaping the poverty cycle.

We should help them along. Micro-credit to the poor, as Yunus has done, is one good way to give the poor opportunities to move up the economic ladder, and kickstart the third-world economy. It would be sad if others extend micro-credit as a profiteering business – every single cent should go to the poor, not into someone’s fat wallet.

Yunus deserves his Nobel. If only others could follow his example – especially those politicians and farmers who sabotaged the Doha trade talks with their selfish demands.

The children in Nigeria deserve better. They’re humans too.

You too can help eradicate poverty. Click here.

--------------------------

English online blog of personal response to current affairs.

Portfolio submission 1 for Term 1

Nigel Fong (3C / 6)

19 February 2007

Word count: 499, excluding endnotes & bibliography.

Endnotes & Bibliography

1. Glossary. The World Bank. Retrieved 20.2.2007, from http://www.worldbank.org/depweb/english/beyond/global/glossary.html#52 Click here

2. A good background reader on and example of donor fatigue: Purtill, Corinne, (2005). Charities fear ‘donor fatigue’. Retrieved 20.7.2007, from http://www.azcentral.com/community/tempe/articles/1012ev-needs12Z10.html Click here

3. Update: The economist article ends by acknowledging rumours that Yunus might enter politics. These rumours turn out to be true. Yunus has formed a political party and entered Bangaladeshi politics. He is a welcome addition to Bangaladeshi's chaotic politcal scene, dominated by 2 women perpertually at loggerheads. There are fears, however, that he might succumb to the corruption that pervades Bangaladeshi politics. Further reading